“The complexity of TMD makes developing a “cook book” impossible,

even though that is precisely what everyone would like.”

Jeffery P. Okeson, DMD

Below is a discussion of several of the most common TMD contributing factors:

• Trauma

Trauma is described as any force to the masticatory structures that exceeds that of normal functional loading. Both intensity and duration are important. There have been many studies that have demonstrated the detrimental effects of trauma, particularly direct trauma. These have shown that the effect of trauma is more profound regarding intracapsular joint structures, as compared to muscular disorders.

Trauma must be sub-divided into macrotrauma and and microtrauma. Macrotrauma would be any sudden force to the face or jaw that could potentially cause structural alterations. Microtrauma refers to repeated small forces to the jaw structures over a long period of time.

Macrotrauma can be further divided into direct trauma, represented by trauma directly to the jaw, and indirect trauma, as possibly represented by a flexion-extension (whiplash) injury to the cervical spine that has been theorized as having an indirect effect of rapid movement of the condyle within the fossa, leading to an intracapsular inflammatory response.

As stated previously, there is ample evidence that direct macrotrauma to the head or jaw can have a significant effect on the development of a TMJ disorder, especially on an intracapsular disorder. In spite of many reported cases of TMD symptoms that have developed post-whiplash injury, the available research does not support the idea that this is the result of an indirect traumatic effect on intracapsular structures. The explanation that is offered to explain the resulting symptoms is heterotopic pain in response to injury to cervical structures. To the experienced clinician, this seems to be an inadequate explanation as to why these patients often develop a profound intracapsular inflammatory response to such injury.

Microtrauma to the temporomandibular joints is usually associated with prolonged clenching and bruxism. A great deal of research has been done on this phenomenon and the process is much too involved to attempt to explain here. However, as Okeson has pointed out, most studies that have been done have looked only at static occlusal relationships and TMD symptoms. There is a need to study the effects of eccentric occlusal relationships, as well as the effect of bruxism in instances of orthopedic instability of the TM joints. This important type of research is nearly absent in the dental literature, perhaps because it is extremely difficult research to do.

• Malocclusion

“The clinician who looks only at occlusion is missing as

much as the clinician who never looks at occlusion”

Jeffery P. Okeson, DMD

A careful assessment of the available scientific literature regarding the causal relationship between dental occlusion and temporomandibular disorders clearly indicates, for multiple reasons, that this causal hypothesis has not been disproven, as has been suggested by certain “experts”. The primary reason is that a very large percentage of the literature related to this question is seriously flawed and does not rise to the stringent requirements of Science to refute the occlusal hypothesis regarding causation. However, thus far there is only limited scientific basis for establishing what, if any, causal relationship does exist.

Multiple occlusal factors have been studied with respect to their potential causal contribution to TMDs. Although many of these studies are flawed in any of several ways, it is worth looking at what factors have been considered. These include:

- • Skeletal anterior open bite

- • Overbite

- • Overjet

- • Cross bite

- • Incisor inclination

- • Missing teeth

- • Posterior occlusal support

- • Balancing-side interferences

- • Working-side interferences

- • Intercuspal interferences

- • Symmetry of contacts in the retruded contact position,

- • Slide between the retruded contact position and the intercuspal position

Very few of these studies considered more than static inter-occlusal relationships upon which to draw conclusions. In addition, only a very small number of studies have considered the relationship between occlusal factors and condylar position. Of particular interest in this respect are studies by Utt et al in Am J. Orthod Dentofac Orthop., Vol.107, 1995, by Crawford in The Angle Orthodontist, Vol. 69 No. 2, 1999, by Girardot in Angle Orthodontist, Vol 71, No. 4, 2001, by Cordray, Am J. Orthod Dentofac. Orthop. Vol. 129, 2006, by Weffort in The Angle Orthodontist, Vol. 80 No. 5, 2010, and by Cordray, Open Journal of Stomotology, Vol 7, 2017 (these articles are available upon request)

In the most recent edition of his text, Management of Temporomandibular Disorders and Occlusion, Okeson cites 57 studies that have looked at the causal relationship between occlusion and TMD. These studies include most, if not all, of the occlusal factors cited above. (However, the studies by Utt, Crawford, Girardot, Weffort, and Cordray, and other similar studies are not included in this group.) Although many of these studies demonstrate design flaws of various types, it is interesting to note that, as presented in this text, the number of studies that showed a correlation between occlusion and TMD is 35 “Yes” findings (Okeson’s assessment) and 22 “No” findings; a ratio of 1.8545:1in favor of a causal correlation.

One of the most prevalent errors in such studies has to do with the number of subjects in the study. Because of the very high prevalence of potentially-significant occlusal factors in the general population, for studies to be able to demonstrate a significant statistical difference between TMD patients and controls, there need to be quite large numbers of subjects in any study. This is referred to as the “Critical Effect Size” of a study.

In the 57 studies cited by Okeson, the size of the studies (number of subjects) varied from 12 to 3428. Because a significant number of these studies have low numbers of subjects, it would seem worthwhile to examine what correlation might be found between occlusion and TMD if only larger studies were considered.

To do this, all studies with less than 200 subjects (number arbitrarily chosen) were excluded and the remaining studies were again compared as to the ratio of “Yes” responses vs. “No” responses. After excluding all studies with less than 200 subjects, there were 29 remaining. Of these, 21 were found to have a positive correlation (“Yes” responses) and 8 were found to have a negative correlation (“No” responses.) This results in a ratio of 2.625:1 in favor of a causal correlation between occlusal factors and TMD

Although this kind of analysis does not prove a clear correlation between occlusion and TMD, it is one of several strongly-suggestive observations that justify further consideration of a possible correlation, particularly of studies similar to that by Utt, Crawford, Girardot, Cordray, and Weffort that consider occlusal factors related to condylar position.

For decades, a common observation has been made by dental clinicians with regard to the use of occlusal appliances in the management of temporomandibular disorders, suggesting that if occlusal appliances are consistently effective in reducing symptoms of TMD, because occlusal appliances alter the occlusal environment, this would seem to imply a correlation between a change in occlusion and a reduction in symptoms.

The problem with this is that the actual role of occlusal appliances in the management of temporomandibular disorders has continued to be debated. It has been suggested that occlusal appliances may have one or more of the following effects, thus complicating the issue considerably:

- • Alteration of the occlusal condition

- • Alteration of the condylar position

- • Increase in the vertical dimension

- • Cognitive awareness

- • Placebo effect

- • Increased peripheral input to the CNS

- • Regression to the mean (from Okeson)

Further complicating this discussion have been several studies that seem to show limited benefit from the use of occlusal appliances in the management of TMD.

The causation of TMDs is clearly not the result of a single factor but a complex and dynamic process that is almost certainly different in each patient. As an experienced TMD clinician, I strongly agree that the clinical evidence for a significant occlusal component to this complex picture, in most patients, cannot be dismissed.

• Parafunction

The dental profession has long been aware that clenching and grinding (bruxism) the teeth can be a cause of pain from the masticatory muscles. Parafunctional activity refers to any activity, not just clenching and grinding, that is not considered functional. Functional activities include chewing, speaking, and swallowing. Parafunction can also include certain oral habits.

It is useful to think of clenching and bruxing as two separate phenomena, those that occur during the day (diurnal) when there is the potential for some conscious control, and those that occur during sleep (nocturnal) when conscious control is not possible. There has been extensive research done on clenching and bruxism. It is beyond the scope of this discussion to address it thoroughly. However, several outstanding articles by some of the most published authors on this subject include [add lit. references re Brux]. We will summarize some of the key points of this research here.

In addition to the possibility that the patient may clench or grind their teeth, other oral habits can be present and often the individual will not be aware of them. These may include cheek and tongue biting, finger and thumb sucking, unusual postural habits, occupation-related activities, and holding objects such as a telephone or violin under their chin. Not uncommonly a person may clench their teeth when concentrating on a task or performing strenuous physical activities. Similarly, this can also occur when a person is driving a car, reading, writing, or typing. It can also occur during the playing of certain musical instruments or when a diver bites for periods of time on a mouthpiece.

Many of these parafunctional activities occur at a subconscious level. For this reason, since the patient is not likely to be aware of doing them, they may deny such activity on a questionnaire or when asked. However, not uncommonly, once they have been asked, they may begin to notice that they do exhibit these behaviors and may later report that they have “caught” themselves doing them. This awareness may be the first step in overcoming activities of this kind that occur during the day and that can be controlled consciously, with some focused attention, during waking hours.

Nocturnal parafunctional behaviors have received a great deal of research attention and appear to be a much different and more complex problem than diurnal bruxism. In spite of the amount of research that has been done, there appear to be contradictory findings. It is thought that some degree of nocturnal bruxism is present in most normal subjects. There was a time when the dental profession was convinced that bruxism was related to occlusal interferences. Research has failed to demonstrate such a relationship. Another commonly held opinion is that bruxism is the result of emotional stress. Although some studies have been able to demonstrate in certain individuals that their bruxing events were closely correlated with stressful events in their lives and that these subsided during periods of decreased stress, this appears to be true of only a small percentage of patients studied.

Nocturnal bruxism is a common phenomenon associated with sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) problems. Effective treatment for such a condition will predictably decrease the frequency and intensity of the related bruxing behavior.

It is also known that certain medications can increase bruxing events.

• Deep Pain Input

This contributing factor occurs when the brainstem is excited by pain, producing protective co-contraction of muscles. This phenomenon is not limited to the masticatory musculature. It occurs throughout the body in response to pain and is a protective response of the body to injury. It can be seen in the masticatory system when, for example, in the presence of a necrotic, painful pulp, the patient may exhibit a limited ability to open the mouth. Once the tooth pain is resolved, the ability to open the mouth typically returns to normal.

The clinician diagnosing a patient with muscle pain and limited range of motion needs to be very aware of this. In addition to pain from an abscessed tooth, other forms of oral pain might include an inflammed operculum, a periodontal abscess, or any other type of common painful dental condition. When there is reason to suspect a condition of this kind, before prescribing treatment for a TMD, the offending dental condition should be addressed and the patient should be re-evaluated for their original presenting symptoms and function after the dental condition is resolved.

This same response is seen with pain originating from the temporomandibular joints. As one of several causes of masticatory muscle hypertonicity, the masticatory muscles will tighten in response to the joint pain. So even in the presence of obvious pain from the TM joints, when there is another source of dental pain present, care must be taken in assuming that the response seen in the muscles is entirely due to pain from the joints. Because resolving the dental pain may be the quickest and easiest problem to address, it is usually best to make that a priority before getting extensively involved in treatment of the TMD.

• The Role of Stress

The relationship between emotional stress and parafunctional behaviors (clenching, bruxism) has long been recognized. Some have considered stress to be the primary cause of bruxism. Although emotional stress can clearly increase parafunctional activity in at least some individuals, the effects of stress on the body and on symptoms of TMDs is a more complex picture.

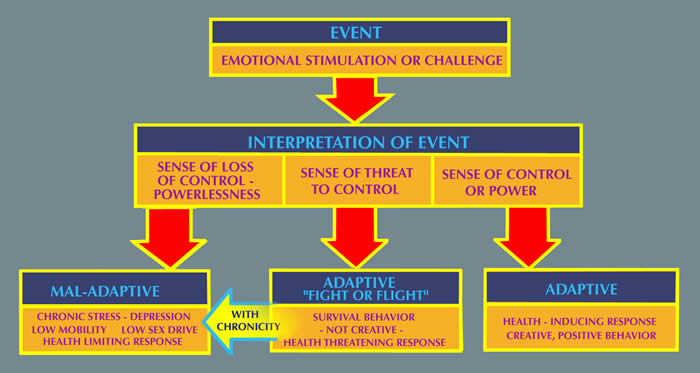

In 1936, Hans Selye first described the General Adaptation Syndrome, explaining how the body responds to the perception of stress. Selye stated that when there was a perception of potential environmental demand (the alarm stage), the adrenal glands produced excess levels of a hormone called cortisol that prepared the body to respond, the so-called “fight – flight response”. Assuming that the threat is overcome, the stress hormones return to normal. However, if the threat persists, the continued production of the stress hormones has a detrimental effect. With chronicity, these can include irritable bowel syndrome, hypertension, certain cardiac arrhythmia disorders, asthma, and an increase in the tonicity of the head and neck musculature. More recent research has shown that this response by the body is a very complex biochemical process.

We have stated that it is the perception of a demand that produces a stress response. How a situation is perceived can vary greatly among different individuals. There are two factors that influence this response. The first involves how much of a demand is perceived in the situation. But equally important is the perception of how much control the individual feels they have in the situation.

Research has shown that situations over which a person perceives that they have limited control produce the greatest stress response. Financial worries, dissatisfaction with a job or other responsibilities, feeling overwhelmed by circumstances, lack of job security, unhappy relationships, etc., are some examples of stress-producing situations that tend to be chronic and persistent.

Whether or not a patient demonstrates evidence of clenching or bruxing their teeth, the effects of stress in their life can cause a great deal of tension in the masticatory muscles, as well as other muscles of the head and neck, due to the biochemical response that directly affects the musculature. When other causes of muscle tension are present, such as dental occlusal factors or pain from the TM joints, this biochemical effect has the potential of an additive stimulus to muscular tension and symptoms.

• Systemic Factors

The systemic pathophysiologic conditions that have potential to affect temporomandibular disorders are extensive and may include degenerative, endocrine, infectious, metabolic, neoplastic, neurologic, rheumatologic and vascular disorders. Conditions involving altered collagen metabolism can also be involved. Their effects can be seen both centrally and locally. When these are present and are recognized as having the potential to affect a TMD, coordination of care with the patient’s primary care physician is recommended.

One of the more commonly occurring systemic conditions that can clearly affect both the causation and the treatment of a TMD is a condition referred to as Systemic Ligamentous Laxity (or Hypermobility Syndrome). Its effect is seen most commonly in patients who demonstrate an internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint. A question that should be asked of all TMD patients is whether they have more joint laxity than other people, or are they “double jointed”. But not infrequently, a patient will deny these descriptive terms and yet demonstrate the condition when tested. The most simple test for determining such laxity is whether they can bend their thumb down to touch their wrist. A positive finding confirms this diagnosis. Their ability to move joints more freely than others will often be seen when measuring their opening range of motion and lateral jaw movements. This laxity appears to be a contributing factor in the development of an internal derangement, although the research is not firm on this question. It appears to be a contributing factor in patients who demonstrate TMJ subluxation, as well as catching or locking of the TM joints. This level of laxity occurs more commonly in women than in men, and is more likely to be seen in younger individuals.

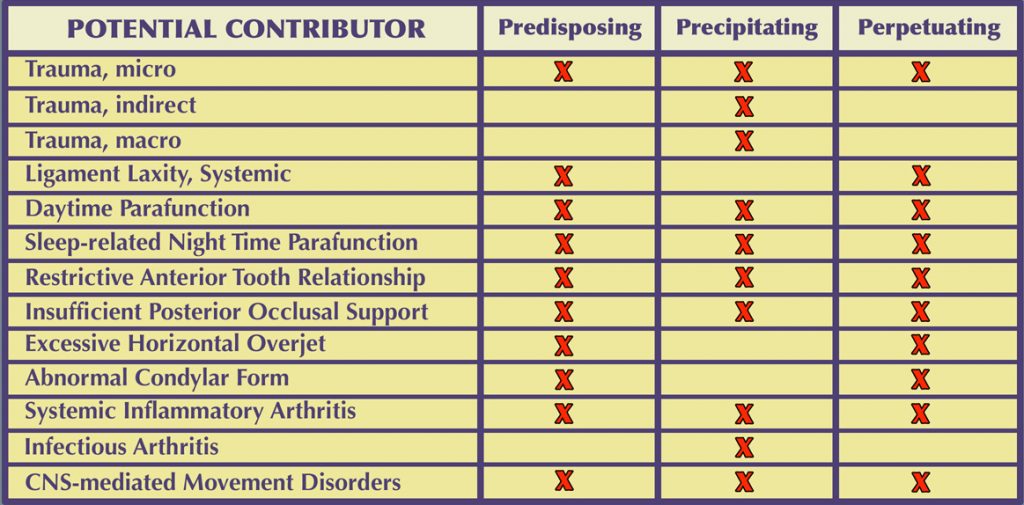

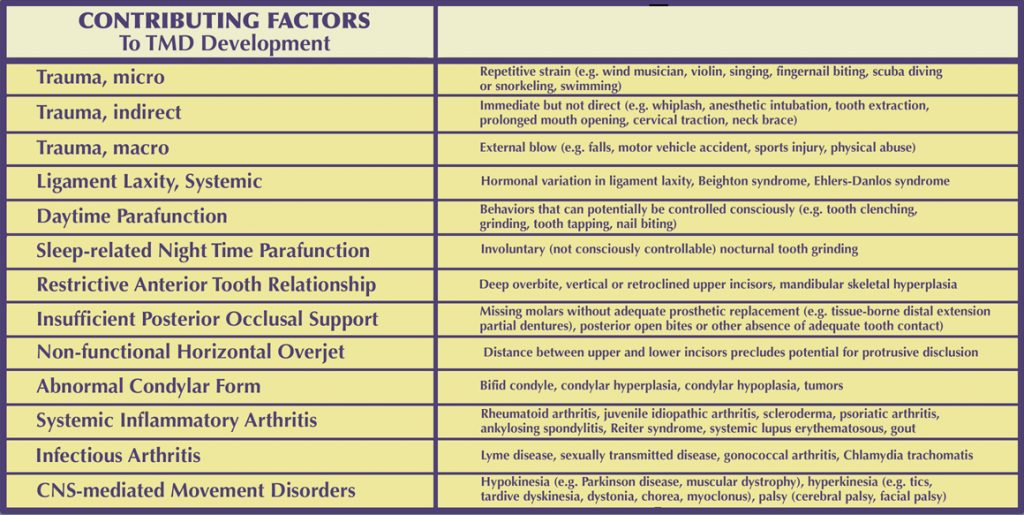

It is useful to categorize the Contributing Factors to TMDs as:

Predisposing — Precipitating — Perpetuating

Predisposing (or risk) factors for TMDs can be:

- • Systemic (affecting the entire body or a particular body system)

- • Psychosocial (interaction of psychological and social variables)

- • Physiologic (cellular and metabolic processes, neuromuscular)

- • Structural (dental occlusion, musculoskeletal, articular, developmental anomalies)

Precipitating (or initiating) factors often involve trauma or overuse. Repetitive activities that maintain the jaw in a sustained or abnormal posture or under abnormal load, such as when playing a wind instrument or violin, can have a precipitating role. Sleep posture can trigger a painful TMD episode.

Perpetuating (or sustaining) factors often include parafunction, overuse, systemic disease, occlusal factors, or psychological distress. These are factors which, in spite of treatment that has reduced the symptoms, may cause the problem to resurface. When possible it is desirable to identify potential perpetuating factors and to reduce or eliminate them. This is the means of minimizing the likelihood that the problem will re-emerge in the future.