What Is The Connection? — a 30 Year Perspective

When I left my dental training, like many dentists even today, I lacked a clear understanding of dental occlusion. My concept of my responsibility to my patients was mostly about teeth and gums. My introduction to classic concepts of dental occlusion began in the early 1970s. But even that training was primarily focused on how teeth should fit together and little about the normal and abnormal function of the jaw system. Those classic perspectives were more mechanical in concept than physiologic. Although that early training was foundational, there was a lot missing.

In those early years there were several shortcomings in our thinking. We tended to think and talk primarily about “ideals” in dental occlusion. There is important value in understanding ideals as general principles. However, the study of dental occlusion has historically tended to be more theoretical than practical and it has been difficult for many dentists to transfer those “ideal” theoretical concepts into practical clinical application.

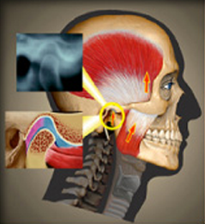

Since perhaps the early 1980’s there has been a progressive and much needed evolution in our understanding, beginning with a new awareness of normal and abnormal temporomandibular joint anatomy and function, that has broadened our perspective of what has been referred to as dental occlusion. For more on TMJ anatomy, see “Anatomy of the Temporomandibular Joints“. More recent thinking is oriented more toward understanding the physiologic function of the entire masticatory system, not just how teeth should fit together. This has included a deeper understanding of the physiology and functional integration of its three key components, the health and function of the temporomandibular joints, the physiology of the muscles that are the primary source of function and loading of that system, and the teeth, through which that loading takes place.

• “To Understand the Abnormal, We Must First Understand the Normal.”

Robert B. Salter, MD

Orthopedic Surgeon

Therefore, the study of Dental Occlusion today is, or should be, the study of the NORMAL function of the entire masticatory system, as well as what is necessary to maintain optimal, healthy function of the entire system. Based on current understanding, it is no longer sufficient to consider only how teeth relate, statically and dynamically.

Contrasted to this is the study of Temporomandibular Disorders, which is the ABNORMAL function (or dysfunction) of the masticatory system. This study includes an understanding of what can go wrong with the anatomy and function of the temporomandibular joints, themselves, as well as abnormal function of the muscles of mastication. Because the teeth are a significant component in the function of this elegant and complex joint system, the study of temporomandibular disorders cannot ignore their role. Our challenge is to understand, in physiologic terms, how the loading of the jaw system, through the teeth, affects the system during both optimal function as well as when the system is not functioning physiologically. Treatment of temporomandibular disorders should be focused on an attempt to restore normal function to the system (or something approaching it), not simply treatment of the symptoms that result from the dysfunction.

• “To Understand Dysfunction, We Must First Understand Function”

Jeffery P. Okeson, DDS

Educator and Author

When we are discussing the physiology and function of the most elegant, complex and misunderstood joint system in the human body, the statement by Dr. Salter, and paraphrased by Dr. Okeson, would seem to be self-evident. And yet, most of us left our dental training uncertain and confused about both normal and abnormal function of the masticatory system and how those subjects relate to day-to-day dental practice.

Fortunately, many of our patients seem to function rather well with what might be considered a pretty significant malocclusion. At least, most of them are not complaining. But when early changes do begin to occur, in the joints or the muscles, that have the potential to lead to greater problems later, often the patient does not recognize these changes or may simply ignore or tolerate them until they become acute. Recognizing these conditions in their incipient state (as with caries, periodontal disease, and oral cancer) offers the best chance of avoiding the sometimes difficult and challenging problems that result from waiting until an acute condition presents itself. A screening procedure can easily be incorporated into any dental practice with minimal additional time involvement. Screening of all dental patients has been recommended by the ADA an several other dental organizations for more than two decades. For more re. TMD screening, see “Screening for TMDs in Dental Practice“.

Earlier it was mentioned that traditional concepts regarding dental occlusion have tended to be theoretical and, therefore, difficult for dentists to incorporate into routine dental practice. A more clinically-friendly way of understanding dental occlusion is to understand it in terms of how the masticatory system is loaded; i.e what constitutes optimal loading of the system that will contribute to maintaining health and minimizing the potential for tissue breakdown? Understanding optimal loading of the system can be applied on a day-to-day basis in dental practice in many different situations and is the basis for evaluating patients on a routine basis (screening) so that potential problems can be recognized before development of an acute condition.

• Occlusion and Temporomandibular Disorders — A Play in 3 Acts

With regard to the role of dental occlusion in temporomandibular disorders, I like to think of it as a play in three acts. This allows us to divide its role into more easily understandable perspectives. The three acts are:

- • Act I — Dental Occlusion as Causation of TMDs

- • Act II — Dental Occlusion in Treatment of TMDs

- • Act III — Dental Occlusion as Potential Perpetuating Factor in TMDs

Act I — Dental Occlusion as Causation of TMDs

This has, of course, been the decades-long debate within the dental profession. In spite of claims that the scientific literature does not support a causative role for dental occlusion regarding temporomandibular disorders, a careful reading of the literature tells a somewhat different story. First, a very large proportion of that literature is flawed in any of several ways and must be excluded from consideration. Only a very small number of studies meet the exacting standards of science with regard to causation. The issues are very complex. Ideal types of studies are very difficult to do and can be limited by ethical constraints. But the bottom line is that there is currently no strong scientific evidence on either side of the debate regarding the role of dental occlusion as a causative factor in TMDs. (a detailed article addressing this issue is available on the office website, TMJOregon.com/article.) However, this does not address the role of dental occlusion with the individual TMD patient.

Act II — Dental Occlusion in Treatment of TMDs

In a review of the literature, Glen Clark found that occlusal appliance therapy was beneficial in from 70 to 90% of TMD patients. When an occlusal appliance is appropriately used in the treatment of a temporomandibular disorder, we are primarily altering the occlusal environment so that the masticatory system is being loaded in an optimum manner. In so doing, we are masking the patient’s native dental occlusion, eliminating any adverse loading factors. This is not to say that appliance therapy is the sole means of treatment or that there are not other factors that could be contributing to the patient’s symptoms. However, with most TMDs, the effects of the use of an occlusal appliance, when used appropriately, are clearly beneficial, allowing us, in most cases, the ability to restore and stabilize physiologic function and homeostasis to the system. The consistency with which this outcome is seen makes it difficult to argue that occlusion plays no role in therapy. However, this observation should not be construed as an assumption that occlusion was the sole or primary causative factor. It may be only one contributor to a more complex clinical picture.

Act III — Dental Occlusion as a Potential Perpetuating Factor

One of the objectives of treatment for a TMD, whenever possible, is to identify factors that may have contributed to the onset of the problem. The rationale for doing this is that any factors that contributed to the onset may have the potential to also contribute to the problem returning if not eliminated. Although in individual patients there may be several factors that have played a contributing role, it may not be possible to alter or eliminate some of them. However, the potential contributing factors that dentists can alter, if they exist, are discrepancies in the dental occlusion. Following resolution of symptoms and stabilization of the jaw, a careful assessment of the dental occlusion should be done. This is typically accomplished with mounted diagnostic casts. Based on this assessment, a plan for the definitive treatment of the dental occlusion, when indicated, can usually be determined. When occlusal treatment is indicated, the nature and degree of treatment can vary widely. The rationale for such treatment is to minimize the likelihood that the dental occlusion will contribute to a return of the patient’s original problem.

My Committment To My Patients

Having addressed patients’ temporomandibular disorders the past 30+ years has given me the opportunity to observe the consistency with which occlusal factors play a significant role in the function and the dysfunction of masticatory physiology. In spite of there being only limited sound support in the scientific literature, (a great deal of it is flawed and does not meet the stringent requirements of Science regarding demonstration of ‘causation’), it is very clear to me that without the incorporation of appropriate occlusal therapy in the management of temporomandibular disorders, we would have very limited ability to resolve these patients’ problems in a definitive manner that will limit their return over time. Treatment that addresses only the symptoms, and not the underlying factors that produce those symptoms, is insufficient.