A common misperception, which tends to be perpetuated by usage in popular media, is that the term “TMJ” represents a distinct, well-defined disorder and that all patients who have “TMJ” are the same or very similar. Within the dental profession that misperception is gradually being understood as such. However, most dentists continue to lack a clear understanding of how patients with temporomandibular disorders (TMD) actually do differ.

Temporomandibular disorders occur as a continuum, from, at one end, relatively minor disturbances of masticatory muscle function (without involvement of the temporomandibular joints) to major structural and functional disturbances of the TM joints at the other end. In addition to the muscles of mastication, there can often be an involvement of other muscles of the head and neck, as well. Across this continuum, the indications for treatment can also vary a great deal, from no treatment at all at the one end, to surgery of the TM joints and subsequent orthopedic rehabilitation of both joint and muscle function, and perhaps the dental occlusion at the other end.

To assure optimum outcomes, appropriate treatment should be based on clearly defined treatment objectives that are consistent with a biologically-specific diagnosis in each patient. Generic “TMJ” treatment, without understanding the actual nature of the underlying problem, is never appropriate. As an example, “let’s try a splint and see if that helps”. When such an approach doesn’t “help”, there may be puzzlement as to why. Therefore, before any treatment is begun, a biologically-specific diagnosis is necessary to determine where on that wide continuum a particular patient’s problem falls.

For dentists who choose not to treat these patients, the process is relatively straight-forward. Once the TMD problem has been identified by means of screening (see “Screening for TMDs in Dental Practice”), all TMD patients will be referred. The process of differential diagnosis then falls to the person who will provide treatment.

For the dentist who chooses to treat some TMD patients but who also recognizes that it may be more appropriate to refer the more difficult ones, doing a preliminary triage of the patient is essential to draw a line between the easier and the more complex TMDs. A decision as to which patients to treat must be based on not only understanding the relative complexity of each patient’s problem, but also on an objective personal assessment of one’s knowledge, skill, and experience, which can only be made by each dentist individually. Before deciding to undertake a full history and examination to determine the biologically-specific diagnosis, some key clinical findings from a screening history and exam will prove helpful in deciding which patients require a more comprehensive work up, prior to undertaking treatment, and which patients should perhaps be referred to a colleague with more knowledge and experience.

The following classification scheme is relatively simple and is intended to compliment the screening process, aiding the dentist in deciding which patients might be treated in their office and which ones should perhaps be referred. The patient types in this classification scheme represent only approximate profiles. As mentioned earlier, TMD patients present along a continuum, without clear lines of demarcation.

Following a screening history and a screening examination, a tentative diagnosis, based on these seven types, can usually be made. A determination regarding which patients you might choose to treat, i.e. the potential complexity of treatment, can only be made after the patient type has been determined.

As suggested earlier, attempting to treat patients using generic approaches is not recommended. When more advanced conditions exist, these can have a potential to worsen in response to certain ill-advised generic treatment approaches. It is recommended that you recognize your personal limits of understanding and only treat patients within your level of knowledge and skill.

• Patient Type 1 — Masticatory Muscle Disorder

Findings from Screening History and Screening Exam

• Muscle pain (myalgia) with or without muscle dysfunction.

• No historical, clinical, or imaging evidence of structural alteration of the TM joints.

(A screening panoramic film with good visualization of the TM joint condyles is desirable but not essential)

– No current joint sounds (click/pop, or crepitation).

– No history of joint sounds.

– No joint pain with palpation, joint loading, or with provocation testing.

Primary Objective of History and Examination

• To rule out joint sounds (click/pop, crepitation), pain or dysfunction, thereby ruling out any involvement of the TM joints.

Caution: A locked joint may not produce any joint sounds. Therefore, also look for evidence of altered range of motion.

There is very little potential risk associated with Type I TMDs. However, response to treatment can vary greatly, determined by whether appropriate treatment strategies are used. Two clinical objectives can be identified that will make a significant difference in patient response to occlusal appliance treatment. First, and most importantly, an occlusal appliance should provide uniform posterior occlusal contact, preferably with cusp tips against a flat surface, not in tooth indentations. Second, the occlusal appliance should allow the potential for mandibular re-posturing to a musculoskeletal condylar position (Okeson). This means that anterior guidance should be quite shallow, rather than steep. Nothing on the appliance should contribute to the patient’s jaw being “locked in” or directed to a fixed position. This type of appliance is generally referred to as a “stabilization” appliance. Dawson uses the term, “permissive”, to describe this appliance design. This type of appliance can also be used as a deprogrammer. Even if there appears to be no involvement of the TM joints in the complaint, some change in jaw posture may be seen as a result of appliance wear. Because closure into the native occlusion (centric occlusion) can cause a deflection of the jaw that may not otherwise have been detected, wearing a “permissive” appliance will mask this deflection and allow the jaw to close without any influence from the teeth. If the joints are able to achieve a more stable musculoskeletal condylar position (Okeson), this change in jaw posture may be desirable. If this type of change is seen, knowing how to properly manage the resulting occlusal effects is crucial.

Following initial fitting and adjustment of the stabilization appliance, follow-up adjustments should be done with the patient sitting upright and no jaw manipulation is indicated. The patient should be instructed to close lightly with the jaw completely relaxed. This encourages a muscularly-determined (musculoskeletal – Okeson) condylar position. The patient is instructed to tap lightly on marking ribbon in this relaxed jaw posture. Adjustments are made, using this approach, until all posterior contacts are reestablished. Follow-up adjustments should occur at fairly frequent visits as long as any change in tooth contact on the appliance is seen from visit to visit. As changes on the appliance decrease between visits, time between visits can be increased. When symptoms are significantly reduced or eliminated and little or no change in tooth contact is seen on the appliance from visit to visit, the patient can be considered “stable”. If achieving this level of stability and decrease in symptoms does not seem to be progressing with only night time wear of an occlusal appliance, full-time wear may need to be considered. If, after wearing the appliance for some period of time, the patient is aware of changes in the native dental occlusion when the appliance is not in the mouth, the nature of this occlusal discrepancy should be evaluated using mounted models and appropriate occlusal treatment options should be considered.

• Patient Type 2 — Capsular and Attachment Tissue Disorders (Joint Sprain)

Findings from Screening History and Screening Exam

• TMJ pain with movement and/or with lateral palpation.

• No historical, clinical, or imaging evidence of joint structural change (click, pop, crepitation).

• This type of joint pain is typically accompanied by masticatory muscle splinting and possible muscle pain.

(A screening panoramic film with good visualization of the TM joint condyles is desirable but not essential)

Primary Objective of History and Examination

• To rule out joint sounds (click/pop, crepitation), or joint dysfunction. If joint sounds are present, this would indicate a disc displacement and would therefore be a Type 3, not a Type 2.

• This type does not include infectious diseases. TMJ infections are uncommon but should be considered as a possibility.

Caution: A locked joint may not produce any joint sounds. Therefore, also look for evidence of altered range of motion.

Capsular pain and inflammation are fairly common. Although these can potentially result from direct injury, such as trauma to the joint, the most common contributor is likely to be parafunction, grinding of the teeth, that puts lateral stress on the joint capsule. Deflective occlusal contacts may also load the joint capsule adversely, contributing to capsular pain. When there is joint pain of any kind, there is likely to also be muscle tightness and pain resulting from muscle splinting (co-contraction).

The clinical approach to this patient type is very similar to Type I. Likewise, there is very little risk associated with capsular pain and accompanying muscle pain, so long as it can be confirmed that there is no other structural damage to the joints, such as an internal derangement. By using a “permissive” stabilization appliance, as described above, uniform posterior occlusal contact is achieved and the potential for lateral loading of the joints is reduced or eliminated. Again, adjustments to the appliance should be done in the manner described above and at a frequency based on the changes that are seen on the appliance. Evidence of improvement will include a significant reduction of subjective symptoms and evidence of a stable jaw position, indicated by a lack of change in occlusal contacts on the appliance from visit to visit. If the majority of bruxism is occurring during sleep, night time wear of the appliance may prove effective. However, full-time wear can be considered if improvement in symptoms is not occurring.

• Patient Type 3a — Disc Displacement With Reduction

Findings from Screening History and Screening Exam

• Evidence (historical, clinical, or imaging) of TM joint structural change (click, pop, crepitation).

• No joint pain during function, or with palpation, loading, or provocation testing.

• With or without muscle pain and/or dysfunction.

• No history or clinical signs of disc interference (catching or locking).

(A screening panoramic film with good visualization of the TM joint condyles is desirable but not essential. However, absence of condylar change does not rule out this type.)

Primary Objective of Examination

• To rule out joint pain and to be sure that the disc displacement is not contributing to problematic joint dysfunction, i.e. disc interference, such as catching or locking that may represent a progressive clinical problem. Careful questioning of the patient regarding catching of one or both joints is critical. If catching is present, this would be a Type 4, not a Type 3.

• Patient Type 3b — Disc Displacement With Reduction

Findings from Screening History and Screening Exam

• Evidence (historical, clinical, or imaging) of TM joint structural change (click, pop, crepitation).

• TM joint pain with palpation, loading, or provocation testing in one or both joints.

• With or without muscle pain and/or dysfunction (when joint pain is present, there will typically be muscle pain, as well, in response to the joint pain; i.e. co-contraction or muscle splinting).

• No history or clinical signs of disc interference (catching or locking).

(A screening panoramic film with good visualization of the TM joint condyles is desirable but not essential. However, absence of condylar change does not rule out this type.)

Primary Objective on Examination

• To rule out the possibility that joint dysfunction, particularly disc interference such as catching, may represent a progressive clinical problem. Careful questioning of the patient regarding catching of one or both joints is critical. If catching is present, this would be a Type 4, not a Type 3.

• Patient Type 3a versus Type 3b

The distinction between these two types is primarily whether there is joint pain with palpation, loading, or provocation testing.

Disc displacement with reduction is an extremely common phenomenon. Studies using history and exam only have demonstrated that between 30 – 40% of the general population has clicking and popping of the TM joints. This finding is nearly always indicative of a disc displacement. In studies that have also used MRI imaging on general population groups (not patients), the occurrence rate increases to somewhere around 75 – 80% of the general population. It is fortunate that most of these individuals do not seek nor need treatment and seem to go on through life with this condition. Most apparently go to their grave with it.

These facts, however, can easily lead to complacency about a finding of clicking, popping, or crepitation sounds from the TM joints. A Type 3a patient (clicking/popping without joint pain) may require no treatment whatever, so long as there is no indication of catching. This would certainly be the most common scenerio. If joint pain is absent but there is muscle pain, treatment would be much like with a Type I TMD. However, mild clicking and popping that is progressively getting louder, in spite of an absence of pain, is almost certainly indicative of a condition that is progressing and may either become painful or, more likely, may progress to catching (Type 4). Therefore, even in the absence of joint pain, when there is evidence of this type of progression, appropriate early intervention is advisable.

A Type 3b patient, on the other hand, will demonstrate clicking/popping together with pain from the TM joint(s) that can be identified with palpation, joint loading, or with provocation testing. This patient will also benefit from a stabilization appliance that provides the potential for muscular re-posturing of the mandible, as described above. So long as there is no evidence of catching (Type 4), most Type 3b patients will respond very well to appropriate occlusal appliance therapy, as with a Type I TMD. Changes in joint position will occur commonly with this type and attention to this and the possible need for occlusal management must be kept in mind when undertaking treatment of Type 3 patients.

It should be quite apparent that making the distinction between a Type 3a and 3b requires not only some careful questioning (is clicking, popping, catching progressing?), but also a fairly simple but critical examination for joint pain. This is where the screening procedure really begins to pay off (see “Early Recognition of Temporomandibular Disorders”).

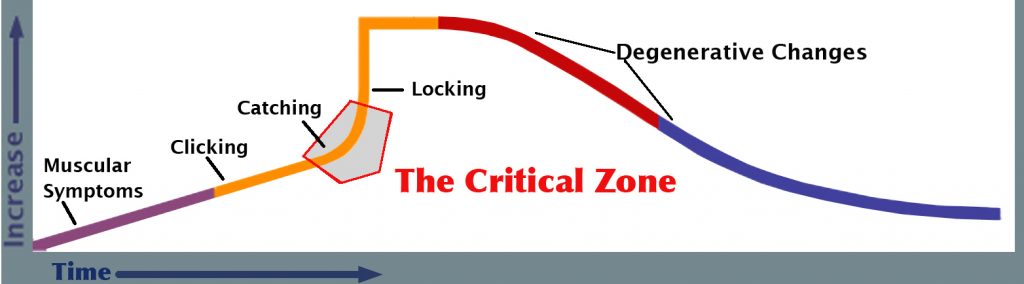

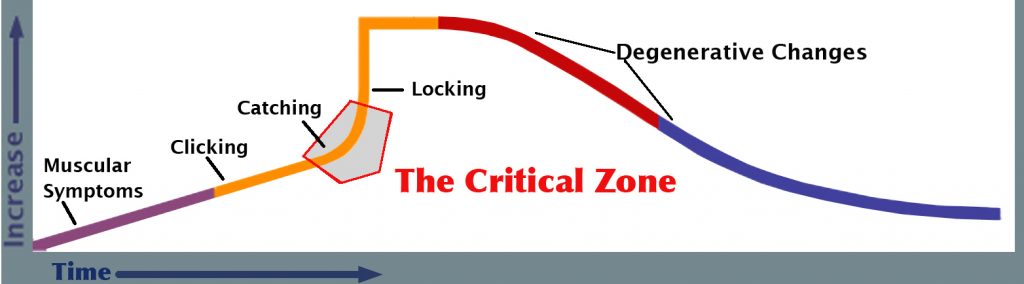

• The Critical Zone

This term is used to designate an area in the continuum of TM disorders in which these conditions can rapidly move from risk-free to high-risk conditions. Being able to determine whether a patient’s TM disorder has entered the Critical Zone requires that the patient be carefully screened by means of the screening history and the screening exam. If this has not been done, the patient can appear to have a relatively minor condition but the condition can potentially worsen very quickly with very unfavorable results.

In discussing Type 3, above, it was mentioned that a patient might appear to be a Type 3a because there is no joint pain. But if the clicking/popping involves even mild catching, or if the clicking/popping has been getting progressively more frequent or louder over time, this is evidence of progression and the joint condition may rapidly move from Type 3a to Type 4 (catching) or even to Type 5 (locking) if the wrong approach to treatment is undertaken.

Therefore, in some cases a Type 3a patient may be in the Critical Zone, in spite of an absence of joint pain.

Similarly, if a Type 3b patient (disc displacement with reduction accompanied by joint pain) demonstrates a progressive increase in the loudness or frequency of clicking/popping or demonstrates even mild catching, an incorrect approach to treatment may be all that is needed to move them rapidly into a Type 4 or a Type 5.

The significant point that needs to be understood is that if the dentist decides to treat a Type 3 patient, they need to be very sure that there is little chance that the treatment that will be provided will not promote a progression to a more advanced condition. That being said, if the appropriate treatment is provided, it is fairly unlikely that the patient’s condition will worsen.

• Patient Type 4 — Disc Catching With Reduction

Findings from Screening History and Screening Exam

• The primary historical and clinical feature is catching but without locking.

• Evidence (historical, clinical, or imaging) of TM joint structural change (click, pop, crepitation).

• With or without muscle pain and/or dysfunction (when joint pain is present, there will typically be muscle pain, as well, in response to the joint pain; i.e. co-contraction or muscle splinting).

• Potential for TM joint pain with palpation, loading, or provocation testing in one or both joints.

(A screening panoramic film with good visualization of the TM joint condyles is desirable but not essential. However, absence of condylar change does not rule out this type.)

The Primary Objective of History and Examination

• To determine the potential that disc interference (catching) may have to progress to a more problematic condition. (See catching sub-categories — “Type 4 – Variability”, below).

• Patient Type 4 — Variability

Catching Presents Along a Continuum

• Grade I Catching: Patient reports brief interference to opening that is easily overcome with minor lateral jaw movement.

• Grade II Catching: Interference is somewhat more problematic but is still overcome fairly easily.

• Grade III Catching: Typically described as intermittent brief locking. Requires more effort to overcome.

The Primary Objective of the Screening History – Questions to Ask the Patient

• How long has the patient been aware of catching?

• Has the catching stayed the same over time or been getting worse? (i.e. catching more frequently or worse?).

The answers to these questions will suggest whether this condition is progressing. When progression is suggested, management must be specific to the condition in an attempt to intercept this tendency to progress.

Patients who are experiencing catching in one or both of their TM joints are usually quite aware of it, but may not volunteer that they have such a condition if there is no associated pain and/or they are easily able to overcome it with a simple movement of their jaw. Again, the importance of the screening questionnaire must be emphasized. If the patient is asked about catching in their TM joints, some will recognize it as catching and others may describe it somewhat differently. Not uncommonly they will say that it feels like their jaw is “going out” or is out of place. Therefore, questioning should be approached in a manner that allows them to provide their own descriptive terminology.

As just mentioned, early catching may be easily overcome and patients may largely ignore it. At this stage, the catching may not significantly interfere with function. However, early (Grade I) catching can easily progress to Grade II or Grade III or even to Type 5 (locking). Effective treatment is most predictable if undertaken at the earliest possible time and becomes rapidly more difficult if the catching is allowed to progress. Therefore, appropriate treatment undertaken when catching is still Grade I will be the most predictable and will be most likely to avoid having the problem progress to a more complex and less treatable condition. At the risk of being redundant, identifying catching when it is at Grade I is only likely to occur if patients are asked very specifically about catching. They are unlikely to volunteer this.

Effective treatment of TM joint catching, with or without pain, requires a level of understanding and experience that most general dentists will not have. Because of the high potential for these conditions to worsen, it is strongly recommended that these patients be referred to someone who has extensive experience in dealing with all types of TMDs.

• Patient Type 5 — Disc Displacement Without Reduction (Joint Locking)

Findings from Screening History and Screening Exam

• Locking, as indicated by history, clinical signs, and/or imaging.

– With or without joint pain.

– With or without muscle pain (when joint pain is present, there will typically be muscle pain, as well, in response to the joint pain; i.e. co-contraction or muscle splinting).

– Joints that have locked have typically passed through Type 4. However, the patient may be unaware that catching had preceded the locking. Locking can also occur acutely in response to trauma, without being preceded by catching. Chronic locking, based on clinical findings, is sometimes seen without any awareness on the part of the patient.

• Joint locking may have an acute onset (recent — hours to days).

Typically, with acute onset, range of motion will be restricted.

• Joint locking may be chronic (occurred months or years ago).

The patient may be unaware that it occurred. Not uncommonly the current range of motion may approach normal.

(A screening panoramic film with good visualization of the TM joint condyles is desirable but not essential. However, absence of condylar change does not rule out this type.)

The Primary Objective of History and Examination

• To determine the degree that locking is interfering with normal function.

• Patient’s age, degree of pain, difficulty with function, both now and in the future, may influence treatment decisions.

This condition is an end-stage outcome of a progressive process, typically represented by preceding Types 3 and 4. It can occur acutely, with the patient aware of a sudden and often significant limitation of range of motion (ROM). It can also occur in a more occult manner with very little awareness on the part of the patient. When occult locking occurs, the articular disc has typically been pushed forward over a long period of time and when the non-reduction occurs, there may be little obvious change in the range of motion. However, if ROM measurements are made it may be noticed, comparing one joint with the other, that there is a difference in the ability of one joint to translate, compared to the other joint. Locking of one or both TM joints may or may not be accompanied by pain.

It seems apparent that locking of the temporomandibular joint is well-tolerated by some patients, particularly if the locking has occurred without notice on the part of the patient, i.e. with little or no associated symptoms. Although degenerative changes within the temporomandibular joints are thought to be associated with progressive changes in the structural integrity of the joint (internal derangements), it is not clear to what degree non-reduction (locking) may predispose the patient to more rapid degenerative changes.

Three primary factors need to be considered is deciding how aggressively to treat a locked joint. TMJ surgery would be the most aggressive treatment option. The first factor that should be considered, quite obviously, is the degree of pain being experienced by the patient. The second, related factor is the degree to which the locked joint is interfering with function. An objective judgment regarding these two factors cannot be made until appropriate non-invasive treatment has been given a chance to reduce symptoms and improve function.

The third factor, in my opinion, is the patient’s age. When a young person experiences an acute locking of the TM joint, because of their projected life expectancy it would seem reasonable to attempt to return the joint to as near normal function as possible to minimize the potential for problems in the future. There is also strong evidence that, in growing individuals, internal derangements have a deleterious effect on mandibular growth. TMJ surgery, when done using a thorough protocol (not just “cut and walk away”) may be indicated and can be very successful, with minimal complications, in nearly all cases. This statement is made based on at least 25 years of experience using a very comprehensive protocol. When careful screening of patients and appropriate treatment protocols are used, both pre-surgically and post-surgically, I have no reservations about recommending TMJ surgery. A complete discussion of TMJ surgery, its indications and objectives, is beyond the scope of this article.

On the other hand, a patient in middle age, with limited symptoms and reasonable function may continue to do well with more conservative treatment. These two hypothetical patients represent the range of variables that should be considered. There is no single treatment protocol that is appropriate in all cases of a locked TM joint. TMJ surgery may be indicated if ROM remains significantly restricted, and/or if pain persists in spite of appropriate non-surgical treatment, particularly when these occur in a younger patient. Less aggressive treatment, such as a stabilization appliance and physical therapy may be appropriate and adequate in other patients.

• Patient Type 6 — Arthropathies (Degenerative Joint Disease, Osteoarthritis, Osteoarthrosis)

Findings from Screening History and Screening Exam

• Early changes, involving primarily soft tissues, may not be evident on imaging.

• Diagnosis is made based primarily on hard-tissue crepitation.

• Joints with arthropathies can be sub-typed.

– Post-traumatic degeneration.

– End-stage progression of internal derangements.

– Age-related degeneration.

• Patient’s age, degree of pain, difficulty with function, both now and in the future, may influence treatment decisions.

(A screening panoramic film with good visualization of the TM joint condyles is desirable but not essential. Condylar change may or may not be apparent in this type.)

The Primary Objective of History and Examination

• Patient Age and History Determine Subtype.

Two factors should be considered before undertaking treatment of degenerative changes in the temporomandibular joints. The first is to consider possible causative factors. The second is to consider whether the degenerative process is quiescent or still active. It is not always easy to determine either of these with confidence. Joints with arthropathies can be sub-typed; post-traumatic degeneration, end-stage progression of internal derangements, or age-related degeneration. The patient’s age, degree of pain, difficulty with function, both now and in the future, may influence treatment decisions. The presence of significant joint sounds; i.e. boney crepitation, or significant changes on imaging are not, in themselves, an indication of a need for treatment. Joints with these findings, indicating significant degenerative changes, can be relatively stable. Therefore, indications of a need for treatment should be based more on pain or significantly altered function, rather than on joint sounds and/or obvious changes as seen on imaging. Significant occlusal dysfunction may be the cause of degenerative changes. However, it is also possible for degenerative joint changes to contribute to the development of a dysfunctional occlusion. Non-invasive treatment should always be considered first. If symptoms can be significantly reduced and a reasonable degree of stability can be achieved, this may constitute adequate treatment.

• Patient Type 7 — Aberration in Form

Aberration in form can include congenital or developmental disorders and most are not associated with orofacial pain. They can be categorized as agenesis, hypoplasia, hyperplasia and neoplasia. Hyperplasias and hypoplasias result in facial skeletal asymmetry as well as bifid condyles and other alterations in condylar form. Although often asymptomatic, non-painful deviation or deflection on opening may be seen. The altered form may be congenital, developmental, or secondary to trauma and is usually unilateral. Definitive diagnosis usually requires imaging.

General Statements, Types 1 – 6

• Historical and clinical assessment is essential when determining patient type. At a minimum, this should be done using a screening approach. This will make possible a determination whether to treat a patient or to refer them. A more comprehensive history and examination is indicated prior to undertaking any treatment.

• With bilateral involvement, designation of patient type should be based on the more advanced side.

• Imaging is seldom necessary to make the determination of patient type.

A screening panoramic film with good visualization of the TM joint condyles is desirable but not essential. More sophisticated imaging, when available, may enhance determination of patient type in some cases, however historical and clinical assessment is nearly always the most reliable basis for establishing a patient type and ultimately, a biologically-specific diagnosis

Conclusion

Each type of TMD represents a unique clinical challenge and must be understood as being clinically distinct from other types. The patient’s long-term best interest is served when their presenting symptoms and other clinical signs are seen as a reflection of the underlying problem, not necessarily as the problem itself. A thorough understanding of their problem, both anatomically and physiologically, will form the basis for addressing the actual problem that is producing the presenting symptoms. When considering which patients to treat and which ones should perhaps be referred, it is worthwhile to consider each patient type individually, as well as personal knowledge, skill, and experience.