“As to methods, there may be a million and then some, but principles are few. The man who grasps principles can successfully select his own methods. The man who tries methods, ignoring principle, is sure to have trouble”

Ralph Waldo Emerson

It should be obvious to anyone involved in health care that to undertake treatment of any condition requires that we first understand what we are treating. In other words, treatment recommendations should always be based upon a specific diagnosis. In the case of Temporomandibular Disorders, “TMJ” is not a diagnosis. The need for a biologically-specific understanding of the condition that is to be treated is crucial; that is the nature of true diagnosis.

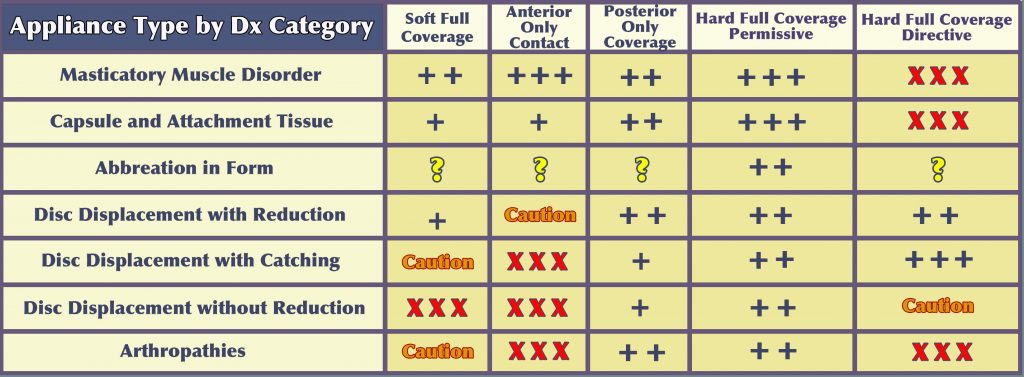

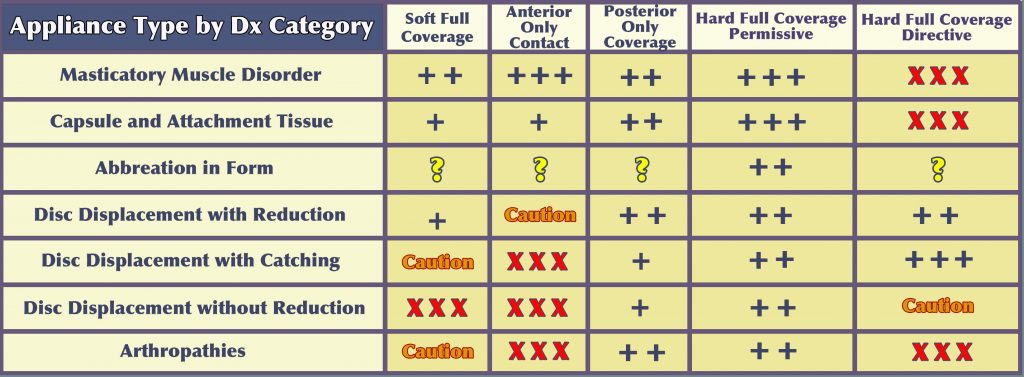

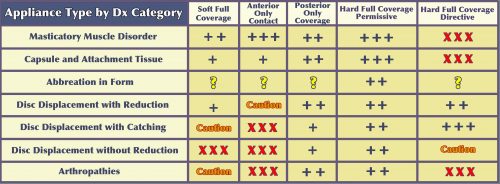

After arriving at a biologically-specific diagnosis, the second requirement, prior to undertaking treatment, is to identify the treatment objectives; what do you hope to accomplish with treatment? In the past, all too often the prevailing treatment objective for Temporomandibular Disorders, whether consciously recognized or not, has been primarily the relief of symptoms and little else. Because pain is what often brings a patient to our offices, the patient’s primary objective will nearly always be pain relief and that is quite understandable. The following table, Appliance Type by Dx Category, serves as a guide for the clinician to tailor the treatment to manage both the symptoms and the underlying problem.

Certainly, if pain is a symptom, then pain relief should be one of the primary objectives of treatment. But pain is often not the actual problem, but rather an expression of the problem. Because treatment has often addressed only the symptoms, and has not addressed the problem that was producing those symptoms, this may largely explain why Temporomandibular Disorders have a reputation for recurring chronically, as this approach often has left the patient predisposed to having the problem return.

Dentists have primary professional responsibility for all disorders of the masticatory system. The treatment of other joint systems of the body is usually provided by several other areas of clinical focus that are oriented toward orthopedic problems. But because of the presence of teeth in this unique joint system, which profoundly affects the function of the muscles and that can also affect both structure and function of the temporomandibular joints, non-dental professional groups are not able to provide the definitive care that this system often requires. If the role of the teeth were not such a significant factor in the function of this system, there would be no unique role for the dental profession in managing temporomandibular disorders.

However, like other joint systems of the body, the masticatory system functions according to certain basic orthopedic physiologic principles. In any treatment that is intended to restore physiologic functional homeostasis to the masticatory system, not simply the treatment of symptoms, this reality regarding orthopedic principles must be appreciated and applied as a part of any comprehensive treatment protocol. Dentists who understand these principles and who are able to meet this standard are engaging in true rehabilitation, not simply symptomatic treatment.

• Patient Self-Management

Having the patient involved in their own care is critical to their understanding of the nature of the problem being managed and how their day-to-day lifestyle and routines may even contribute to the problem. Developing a relationship with the patient that promotes a “therapeutic partnership” and negates the “fix me doctor” mentality will always be beneficial and often contributes to optimum outcomes. The keys to patient involvement include motivation, cooperation, and compliance.

The objectives of a successful self-management program are to promote healing and to prevent further injury to the musculoskeletal system. To be effective, this will require guidance and counseling and continued monitoring for progress and problems during the course of treatment. It should involve voluntary limitation of mandibular function, habit awareness and modification, and incorporation of a home physiotherapy program.

Modification of Functional Behavior

• Avoidance of heavy mastication, gum chewing, wide yawning, and singing.

Habit Awareness and Reversal of Parafunctional Behaviors

• Clenching, bruxing, tongue thrusting, cheek biting, poor sleeping posture, ergonomic issues when sitting, object biting, and playing some musical instruments.

Incorporating a Home Physiotherapy Program

• This can include posture training, range of motion exercises, mobilization, application of heat and/or cold, and massage.

Guidance and instruction in all of the above is often most effective if provided by a trained physical therapist with particular knowledge, skill, and experience in masticatory musculoskeletal problems. A physical therapist with these skills will evaluate the patient, not just with respect to what is going on with their jaw, but will look at them from a wider perspective. They can also provide other physical agents and modalities such as electrotherapy, ultrasound, iontophoresis, etc. that will further enhance the therapeutic response. Close communication with the physical therapist will allow the dentist to reinforce what is being provided by the physical therapist.

• Behavioral Therapies

• Research has been done regarding two major behavioral factors, personality traits and emotional states, as they might be related to causation of TMDs.

Personality Traits

Personality traits are considered to be more or less permanent features in individuals. Multiple studies have attempted to identify personality traits that are common to TMD patients. Many personality traits have been tested. Various studies have reported a relationship of this kind but the enormous variation of traits that supposedly demonstrate a correlation makes it impossible to conclude that any one or several traits predominate as common in and /or contributory to TMDs. Taken as a whole, TMD patients demonstrate a normal range of personality traits. Therefore, no personality trait test will aid in selecting treatment for an individual patient.

Emotional States

Emotional states, unlike personality traits, are usually of short duration in human behavior. Here, more consistent research results have been reported. In most studies, high levels of anxiety have been common in TMD patients. These studies have not been able to show whether anxiety is a contributor to the symptoms or has been the result of the pain. Both could be true. Other emotions that have been reported have been apprehension, frustration, hostility, anger and fear. This does not imply, however, that all, or even most, TMD patients exhibit such emotional states.

Although increases in emotional stress in some studies has been associated with increased parafunctional activity (clenching, bruxism), not all studies have demonstrated this association. An increase in muscle tonicity may also result from activation of the sympathetic nervous system that occurs with emotional states. Unfortunately, as with personality traits, no psychologic tests are able to determine whether these emotional states are contributing to muscle hyperactivity nor can they help in determining appropriate treatment.

Another emotional state that has been related to TMD is depression. Again, the presence of depression does not necessarily imply that it is the cause of the TMD symptoms. In fact, when a painful condition has become chronic, it is known that depression can be the result of the chronic pain, rather than the other way around. It is possible that pain and depression may co-exist without being related. If this appears to be the case, particularly if there also appear to be dental contributors, then the two conditions should be addressed simultaneously.

It is also known that a history of physical and/or sexual abuse (particularly in women) is linked to chronic facial pain, including headache. In some patients, a history of abuse can lead to post-traumatic stress disorder that contributes to an up-regulation of the autonomic nervous system, thus decreasing the body’s ability to overcome new challenges, both physical and psychological.

There is a common myth within the dental community that patients with TMD symptoms are somehow emotional invalids. This is unfortunate, because it is generally untrue. However, it is important for dentists to be aware that emotional states and/or a history of emotional trauma, when present, can play a role in the expression of a patient’s TMD symptoms. When appropriate dental approaches to treatment have not produced anticipated outcomes, consideration of the possibility of an emotional component should not be dismissed.

The challenge for a dentist, when emotional stress is suspected, is to know whether this is a result of stress from daily routines or from deeper, more profound emotional issues, in which case referral to a properly trained therapist may be indicated. Initially, however, several techniques that can address the causes of more common sources of stress can be considered. It is useful to introduce a discussion of these at the beginning of any treatment regimen, for all patients.

There are difficulties in evaluating the role of emotional stress in TMDs. Therefore, other than the stress reduction methods described here, it is usually advisable to rule out all other contributing factors before considering making a referral to a trained professional for extensive emotional therapy.

• Pharmacotherapy

Pharmacotherapy can play an important role in the management of TMD symptoms. It is important to emphasize again, however, that the objective of treatment should not be simply symptom management but rather the identification and management of the underlying problem that is contributing to the symptoms. In that respect, pharmacotherapy should play a limited, and hopefully a short term role in the overall management of TMDs. Other therapies will be the means of addressing the actual problem that is causing the symptoms and the emphasis of treatment should be on those therapies, once the actual condition is identified (diagnosis) and reasonable treatment objectives determined and undertaken.

The medications that are most likely to be abused are narcotics and tranquilizers. To the degree that is reasonable in the individual case, the use of narcotic analgesics and tranquilizers should be very limited. In most cases of TMD management, these stronger medications should not be required at all. If there is indication for their use, they should not be prescribed on a “prn” basis. It is recommended that these drugs, when required, be prescribed to be taken at regular intervals for a prescribed period of time, and only in conjunction with other therapies. If the patient is unable or unwilling to undertake therapies that are likely to address the actual underlying problem, prescribing narcotic analgesics and tranquilizers is usually contraindicated to avoid the patient becoming reliant on medications in lieu of more appropriate treatment.

The medications most commonly used in TMD management include analgesics, anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroids, anxiolytic agents, muscle relaxants, antidepressants, and local anesthetics.

• Physical Medicine

Dental professionals typically have had minimal exposure to the benefits that can derive from utilizing physical therapy and other forms of physical medicine as an adjunct to dental treatments in the management of temporomandibular disorders.

It is important to recognize two distinct possible approaches to treatment of Temporomandibular Disorders, as well as all musculoskeletal pain/dysfunction. Because pain is most typically what causes patients to seek treatment, arguably the most common approach to treatment of such disorders is to focus entirely on reduction of the pain symptoms. Therefore, when a clinician (dentist or physical therapist) achieves a degree of symptomatic relief, they may consider their treatment to have been successful. However, with nearly all musculoskeletal disorders, regardless of where they may occur, the pain symptoms are typically not the problem but are an expression of underlying problems.

Definitive treatment addresses the underlying cause of the symptoms in an attempt to restore more normal function with the objective of minimizing the likelihood that the problem will chronically recur. This is true rehabilitation. Throughout this web site, all discussions of treatment have an underlying principal; the concept that rehabilitative treatment is preferable to treatment that is simply focused on symptomatic relief.

Experience and the literature has clearly shown that effective treatment provided by a dentist that is combined with expert physical medicine can usually produce more predictable, lasting, and optimum results than either of these alone for patients with Temporomandibular Disorders. We strongly encourage dentists treating Temporomandibular Disorders to develop a professional working relationship with a physical therapist or other manual therapist who is experienced in the management of Temporomandibular Disorders.

• Occlusal Appliance Therapy

Throughout dental literature related to the treatment of TMD, the modality that is advocated nearly universally is the use of occlusal appliances, commonly referred to as “splints”. A wide variety of designs of occlusal appliances are known to be useful and effective in the treatment of most TM disorders. A number of theories have been suggested as to why occlusal appliances are effective in reducing the symptoms associated with TMDs. However the mechanisms that are involved have not yet been scientifically documented. Many experienced and respected clinicians, over many decades, have made similar observations and have come to similar conclusions regarding the effectiveness of occlusal appliances. Regardless of how consistent the clinical experience may be, without sufficient scientific data to support any of these theories, conclusions based on clinical observation alone must still be considered “anecdotal”.

The following table of recommendations for Appliance Type by Diagnostic Category is based upon the clinical experience of Dr. Higdon.

Any plastic device that is placed between the teeth, regardless of its design or the material of which it is made, alters the occlusal environment in some way. The consistency of the observations of respected clinicians implies that favorable physiologic adaptation is responsible for producing favorable improvement. Understanding these physiologic mechanisms, based on a biologically-specific diagnosis of the individual patient’s presenting condition, is the basis for consistent effective use of occlusal appliances. It is essential to avoid hit-and-miss, trial-and-error “appliance therapy” that too commonly occurs as a result of inadequate understanding and training. We must ask ourselves, “What is the disharmony within the masticatory mechanism that needs to be altered to achieve the desired treatment objectives?”

Some patients will state, “I’ve tried ’splints’ and they haven’t worked”, meaning “Don’t tell me that you want to do that to me again.” A common misperception, not only on the part of some patients and insurances companies but, surprisingly, on the part of quite a few dentists, is that if the patient has ever been fitted with a piece of plastic in their mouth, they have had effective splint therapy. There is no magic in the plastic itself and an intraoral appliance is no more than a tool that requires knowledge, skill, and experience to achieve a quality outcome.

If the major problem to be addressed is predominantly muscular in nature, without a significant involvement of the temporomandibular joints, then we need to understand which appliance design can produce a positive muscular response. If, on the other hand, the problem that needs to be addressed involves the temporomandibular joints, one needs to know as specifically as possible what the diagnostic category of that joint condition is to be able to decide on an appropriate design for the appliance. It should be mentioned that when there is a significant joint component to the problem, there will almost always be a muscular component that must also be addressed. So in appliance design, the muscular component must always be considered.

In most cases, problems that involve primarily the muscles are relatively easy to address. Once the joints have become a part of the problem, the level of challenge increases and it becomes extremely important to appreciate the degree of joint involvement. On the low end, it may involve apparently uncomplicated clicking and popping without pain. However, even painless clicking does tell us something about the structural condition of the joint(s) and should not be treated as inconsequential when selecting an appliance design.

When clicking and popping of the TMJs is accompanied by pain arising from the joints, the clinician must then consider what in the design of the occlusal appliance will most effectively address the joint pain as well as the inevitable reflex muscular splinting and pain that will accompany it.

If the patient is describing catching of one or both joints, whether or not there is pain from the joints, the TMJ dysfunction has now escalated to an even more critical phase. (See Diagnosis —> Diagnostic Categories —> Variability, Progression and the Critical Zone) Catching can progress to locking, sometimes very quickly. Therefore, addressing the catching at an early stage becomes quite important. In this instance, further consideration of appliance design and how much the appliance is to be worn by the patient become even more critical. Certain types of appliances, such as anterior deprogramers, the B splint, and the NTI, are clearly contraindicated for catching joints and can actually contribute to the joint progressing to locking.

Regardless of the presentation of the patient’s problem, the best clinical judgment results from a thorough history and a careful examination and sometimes sophisticated imaging. Shooting from the hip in selecting an appliance design, without a careful assessment and a reasonable biologically-specific diagnosis, can lead not only to a lack of improvement but the potential for a problem actually worsening, perhaps as a result of an inappropriate treatment choice.

• Occlusal Therapies

Occlusal Treatment — When, Why?

A decades-long discussion (debate) has existed regarding whether occlusal treatment of any kind is necessary or appropriate related to temporomandibular disorders. This debate can be deconstructed into several related questions:?

1) Is there a relationship between dental occlusion and temporomandibular disorders?

2) If such a relationship exists, does dental occlusion play a causative role in TMDs?

3) If a causative role has not been clearly established, what is the rationale for doing occlusal treatment?

4) If occlusal treatment is indicated, when is it appropriate?

Each of these questions is discussed very thoroughly in the section, “Occlusal Treatment — When? Why?”. Please click on this link

• Surgical Management

A specific subset of TMJ disorders including internal derangement, degenerative joint disease, rheumatoid arthritis, infectious arthritis, synovial chondromatosis, ankylosis, recurrent mandibular dislocation and condylar hyperplasia and hypoplasia are all amenable to surgical intervention.

The decision to perform TMJ surgery must be based upon firm clinical and imaging evidence that a mechanical disruption of the joint structures has occurred and that the degree of limitation in function that has been imposed on the patient justifies the surgery. While TMJ surgery usually does reduce the patient’s daily pain level, TMJ surgery should never be done solely to relieve pain in the absence of significant functional impairment. If the pain is generally well localized to the side of the face, if this pain is increased with TMJ function, and if the patient has not obtained adequate relief from an appropriate nonsurgical treatment protocol [including but not limited to physical therapy, altered diet, medications and an intraoral appliance], then this patient may represent a surgical candidate.

At this stage in treatment planning it is important to determine if the patient should not be considered as a surgical candidate for other reasons. The psychosocial aspect of chronic facial pain must be considered and the surgeon should evaluate the emotional influences on cognitive processes such as decision-making. A patient’s emotional instability, habituation to pain medications, or an impaired cognitive state are all reasons to not consider the patient an appropriate surgical candidate, despite clinical evidence of the patient presenting with a TMJ surgical indication.

In some situations the need for TMJ surgery is unequivocal, such as tumors and neoplasms of the joint, as well as selected fractures of the condyle. There are other situations, involving impaired function that is not accompanied by pain, yet TMJ surgical intervention may be indicated. These include intracapsular conditions such as aberrant growth (hyperplasia/hypoplasia), ectopic bone formation, synovial chondromatosis, and intracapsular ankylosis, as well as extracapsular conditions such as coronoid elongation. The preceding conditions are not likely to respond to the nonsurgical protocol described above. When any of these condition progressively worsen, resulting in significantly impaired jaw function, a surgical consultation is advised.

It is helpful to explain to the patient that all TMJ surgery is a “controlled injury” in that multiple healthy tissues and structures are impacted during access to the temporomandibular joint, and that surgery poses risk of nerve damage, scar tissue formation and infection. The anticipated benefits of the surgery must outweigh the risk. It should never be stated that the surgical procedure will provide a “cure”, but rather that it has the potential to facilitate the rehabilitation of their TMJ- related pain and dysfunction to a more functional state.